Digital embodiment: Constructing and deconstructing the body [Part 2]

Read part 1 of the presentation

I think about embodiment from an educational perspective. You’re probably thinking, what does this have to do with education? Why does this matter in education? As you know, the digital is part of education now. Most institutions offer some forms of digital learning (broadly defined–anything from learning management systems, to digital tools like hypothes.is, to domain of one’s own initiatives, and more) yet few tackle questions about teachers’ and students’ embodiment in those digital spaces. What does a learning management system or a Facebook group mean for students’ embodiment? What about a videoconferencing-based class? How do we think about embodiment in that space?

I want to step back into a time when digital learning wasn’t so pervasive. Because, believe it or not, embodiment was a tricky notion before digital learning.

Education has long suffered from dualism, or the mind/body split. The mind/body split is the belief that the stuff of the mind–thoughts, knowledge–is independent of the body. Education’s interest has largely been with the mind. Develop the mind. Ignore the body. Or, in its more innocuous form: focus the mind—what does the body have to do with anything? You see this in strands of cognitivism. Framing of the mind and the memory as computers—with input, output, storage, processing capacities, etc. The body in those theoretical frameworks is considered only to the extent that it limits or allows storage, retrieval, and processing. People who subscribe to these theories will also think of computers as ways to extend the mind but without really attending to the social and political implications of that extension.

Many researchers and educators, however, believe that knowledge is embodied. From Vygotsky to George Lakoff, there has been a recognition of the role that the body, and embodiment, play in learning and in knowing. Critical educational theorists have also talked about the ways in which the body—and its recognition or ignoring–is political in the context of learning.

In We Make the Road by Walking, critical educator and writer Paulo Freire wrote: “Knowing for me is not a neutral act, not only from the political point of view, but from the point of view of my body, my sensual body. It is full of feelings, of emotions, of tastes.” Freire acknowledges that learning is both part of a political framework and that his sensual body shapes what he knows, why and how he knows it. Side note: I will try to return to the “sensual body” in a later post, as I have developing thoughts on this.

bell hooks addresses dualism in a must-read chapter in Teaching to Transgress: “I think that one of the unspoken discomforts surrounding the way a discourse of race and gender, class and sexual practice has disrupted the academy is precisely the challenge to that mind/body split. Once we start talking in the classroom about the body and about how we live in our bodies, we’re automatically challenging the way power has orchestrated itself in that particular institutional space.

The person who is most powerful has the privilege of denying their body.”

Social justice is addressed in bodied education. It’s a privilege to ignore the body—the privilege of neutrality is given to white male bodies. And by not addressing that in our classrooms, we are perpetuating the power structures, political and social inequities, that exist outside of our classrooms. We are not addressing the embodied learning needs of our students.

And as I said before, just because we move parts of education into the digital, doesn’t mean the body becomes less important. As my colleague Audrey Watters wrote: “bodies matter when we learn; communities and affinity and situatedness matter; digital learning, even though some of it is “virtual,” does not – or should not – change that.” (Audrey’s piece was a reflection on a talk given by Tressie McMillan Cottom. You should immediately follow both women on Twitter, if you aren’t already. @audreywatters and @tressiemcphd)

I know most of you don’t work in education, but I wanted to tell you about my lens because I think it’s helpful. As I said before, our work, whether it’s in education or in something else, our personal lives, our connections, are inherently hybrid. We would do well to attend to embodiment. We would do well to think about the ways we treat embodied beings, both in physical settings and digital. We would do well to question how embodiment privileges some, and disempowers others, both in physical and digital settings.

I’m going to tell you two stories. One should scare the hell out of you. One should give you some practical ideas to reflect and work on. The first is about digital redlining.

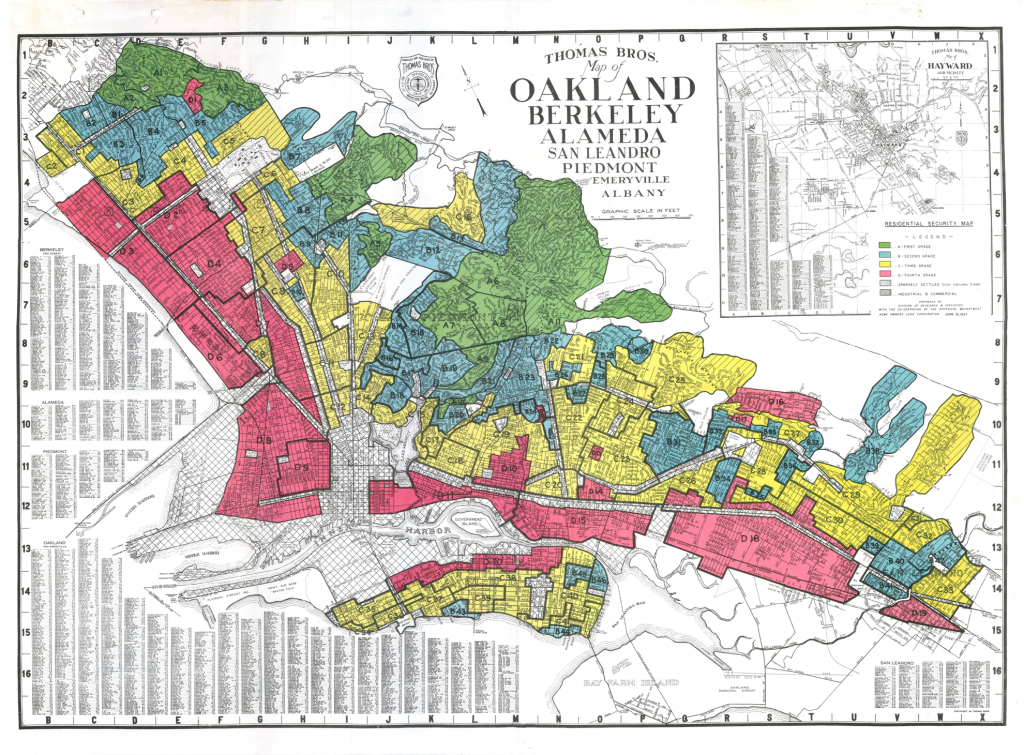

Redlining was coined by John McKnight in the 1960s and defined as policies and practices that deny services, either directly denying access or by making services overly difficult to access (via pricing, weak or no infrastructure, etc.), as a form of discrimination against communities of color. In the United States, redlining was first institutionalized via the National Housing Act of 1934, which allowed for the creation of color-coded maps, called HOLC maps, that identified where mortgages and financial services could be differentially offered, based on the racial and socioeconomic composition of those communities (from Gilliard’s Common Sense article). Beyond redlining for financial services, we see redlining of health care services, access to fresh foods (creating food deserts in urban areas), and more. Redlining can happen through design. Robert Moses who designed parts of New York City between 1930s to 1960s used bridge height to keep people of color out of certain parts of the city by making bridges too low for public buses to enter those areas (h/t to Mike Caulfield’s wikity).

Redlining is an embodied practice. It is discrimination based on bodies. And it doesn’t just happen in physical spaces. Ignoring the body in digital spaces is a problem because it obscures the ways in which the body is used to deny access, to keep certain people out.

I was introduced to digital redlining by my colleague Chris Gilliard, who has done really great research on the topic. Chris defines digital redlining as “tech policies, practices, pedagogy, and investment decisions that reinforce class and race boundaries.” (quote from the Teaching in Higher Ed podcast featuring Chris)

It may be as simple as digital redlining in Pokemon Go. When Pokemon Go exploded into popular use, people in urban areas began reporting that their communities lacked Pokemon stops. Now I know you’re thinking: Pokemon Go, really? Yes, really. As Penn Law professor Jeffrey Vagle wrote: “Yes, Pokémon Go is just another silly smartphone game. But through its popularity and usage patterns, we can see the very real boundaries of poverty and racism that continue to be reinforced when we should be using our technologies to dismantle them.” (via USA Today)

Digital redlining might be Facebook removing posts and closing accounts of people raising awareness about issues facing black bodies. This happened to a well known writer, Son of Baldwin, who posted an article called Dear Black Folk on Facebook. I read about this incident in an article by Tressie McMillan Cottom, called Digital Redlining After Trump: Real Names + Fake News on Facebook. Tressie quotes Son of Baldwin: “It was a relatively non-controversial post in which I outline the disparities between how black people and white people are treated in a white supremacist society.” Racist people reported the post and the post and the writer were banned—albeit temporarily—from facebook. I know you have seen racist rants on Facebook. Why is it that only some get banned? Facebook’s Actual Name policy is digital redlining at work. Go look up that policy and read Tressie’s article about it.

Digital redlining may involve companies not providing infrastructure as services—like Amazon Prime delivery and Google Fiber networks–to low-income communities or communities of color. Digital redlining may be as ugly as AirBnB hosts denying rooms to people based on race, sexuality, or religion.

It gets worse. In May of last year, Taylor and Sadowski published an article in The Nation titled: “How Companies Turn Your Facebook Activity Into a Credit Score.” The article told the story of Nicole, a student drowning in debt after receiving a worthless and expensive degree from a predatory for-profit university. Facebook began showing her ads about debt refinancing, debt relief. She called a company listed in one of the ads and immediately found herself having to protect even more personal information, like her SSN, bank info, etc. Here is a quote from the Nation article: “’Just as neighborhoods can serve as a proxy for racial or ethnic identity, there are new worries that big data technologies could be used to digitally redline unwanted groups, either as customers, employees, tenants, or recipients of credit,’ a 2014 White House report on big data warns. Thus, rather than overt discrimination, companies can smuggle proxies for race, sex, indebtedness, and so on into big-data sets and then draw correlations and conclusions that have discriminatory effects.” The article goes on to talk about how banking entities are partnering with tech companies that hold a lot of embodied data about people to help them formulate lending practices for particular “kinds” of people.

A version of this happens at colleges and universities, too. Schools that serve poor communities and communities of color, are more likely to regulate, track, and throttle students’ access to information and tools on the web, according to Chris Gilliard’s research. Chris wrote:

“Digital redlining arises out of policies that regulate and track students’ engagement with information technology. Acceptable use policies (AUPs) are central to regulating this engagement. To better understand how digital redlining works at community colleges, we sampled acceptable use policies from across the range of Carnegie Classifications. These policies, like the HOLC maps, create boundaries. The boundaries not only control information access and filtering, but also they determine methods of collection and retention of student data and how data is passed on to third parties. The modern filter not only limits access to knowledge, but it also tracks when people knock against these limits. In this environment, curiosity looks a lot like transgression.”

It may still get worse. Because, under this new administration, net neutrality is at greater risk than ever. Net neutrality is a principle of ensuring equal access to the internet and internet services; this principle helps to keep certain kinds of digital redlining at bay. We now have Trump’s pick to head up the FCC, Federal Communications Commission, who has worked to roll back consumer regulation protections that help prevent redlining.

Why does digital redlining happen? Is it always intentional or malicious? Often, yes, but sometimes it falls under control and protect missions of institutions (like schools). Remember, however, the racial and gender composition of many Silicon Valley tech companies. “Technology largely developed by white men is full of assumptions that are just not true or helpful when used in more diverse or complex environments,” Nathan Freitas, a fellow at the Berkman-Klein Center at Harvard University was quoted in this USA Today article. Remember that white bodies have the privilege of denying their white bodies. As long as racism and other isms exist, prejudices and discrimination will be built into our technologies.

In the next post, I will share more about our experiences dealing with embodiment at Middlebury.

Much appreciation for this thoughtful series, Amy. The trap of one’s abundance / paucity of privilege is the amount you have is inversely proportional to your awareness of it, and that itself flips back inversely to one’s ability to affect a change. Identifying the abundance side leads to assertions of “I’m the least ________ person there is”.

I’m intrigued by the concept of embodiment, as it hopefully has one grapple with how thoughts, ideas, actions, are not unconnected from our physical selves. The ability digitally for one’s responsibility for thoughts, ideas, actions to be separated from our bodies (hidden identity, more separation from the people it affects) is a two-side edge, that is just driving deeper over time, rather than bringing together.

One of the more disturbing practices I learned from Chris’s work (the list is long) is Stingray technology, where response by police, medical personnel is red-lined gauged by geolocation of mobile phones. I did not need to zoom in on the maps of my home city of Baltimore to know what the different colors mean. Again, when you are not affected by the practice, you have no idea it’s there. When you are affected, you know it’s there and also that there’s little you can do.

How the awareness/impact relation is ever changed hinges perhaps on understanding not only our own embodiment but others. And that is a monumental thing to take on.