Not-yetness and learnification

Video and notes from my keynote at the Digital Pedagogy Lab in Cairo, Egypt, hosted by the American University in Cairo. Thanks to Maha Bali, our amazing and gracious host, and to AUC for putting together this delightful event.

Click here or on the image above to view the video of the talk, Not-yetness

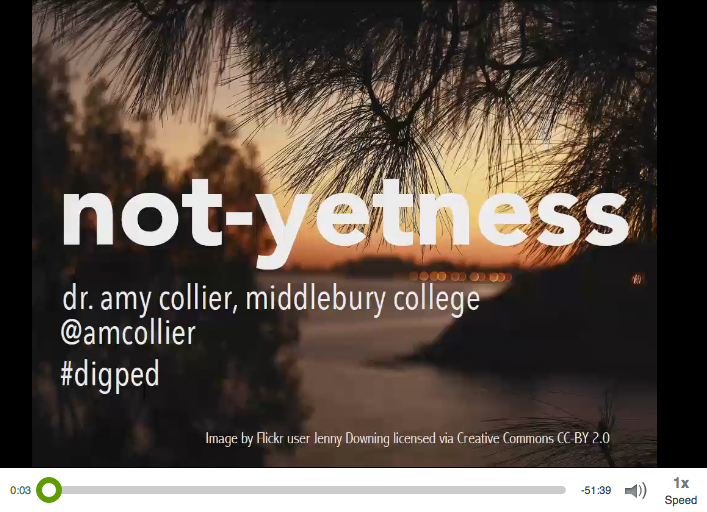

In 1995, Bob Barr and John Tagg wrote a seminal article on what they saw as a major paradigm shift in education: The move from teaching to learning. Barr and Tagg weren’t the first talk about learning within education in this way. In fact, when they wrote about it, a large shift was already underway. Philip Kerr, writing about the shift, shared this graph which shows the instances of the words teaching and learning over time and, as you can see, the shift had hit the accelerator in the late 1980s:

Gert Biesta calls this the “learnification of education.” The shift is largely seen as a good thing—it’s hard not to. Of course we want our students to learn. But this shift to learning is about more than just a paradigm shift toward student-centeredness. Remember what Paulo Freire said, that our language and approaches in education are not neutral. What if we ask what’s at stake in the learnification of education? What if we do not assume that this shift toward learning is automatically a good thing? What if we ask critical questions about what the shift means and how it plays out in education more broadly today?

The move towards learnification co-occurs with a number of socio-political turns, including: neo-liberal individualism, a burgeoning age of accountability that narrowly defines education to arrive at assessments of its value (and consequently the value of those who pursue education), and, as Haugsbakk & Nordkvelle point out, the proliferation of instructional technologies into education and an overly-positive view about the role of technology in education. An uncritical look at the movement toward learning ignores the interplay of these and many other factors at play in education.

According to Biesta, the outcome of the learnification of education may be devastating. Learning becomes a decontextualized individual activity, rather than a communal and situated activity that is connected to a purpose. The why and for what purpose people seek education becomes lost or obscured in learnification.

Learnification has also meant decomplexifying the stuff of education. Input-output. If learning becomes the sole goal, this unsituated individual activity, we can target bite-sized learning activities and easily measure those to talk about productivity and effectives. Learning becomes input-output. We get “learning engineers.” We get “evidence-based practices” and the learning sciences. We get the Undersecretary of Education in the U.S. saying:

Source: Campus Technology

We see this too in the way educational technologies are sold to teachers & administrators. This product will make learning easier. This will engage your students in learning. Quick, easy, simple. Data about learners’ mind states. Personalization. Words that get pulled into conversations about the role of technology in education. As George Siemens pointed out at a conference we attended a few years ago, it becomes the language that we use to talk about weight loss diets.

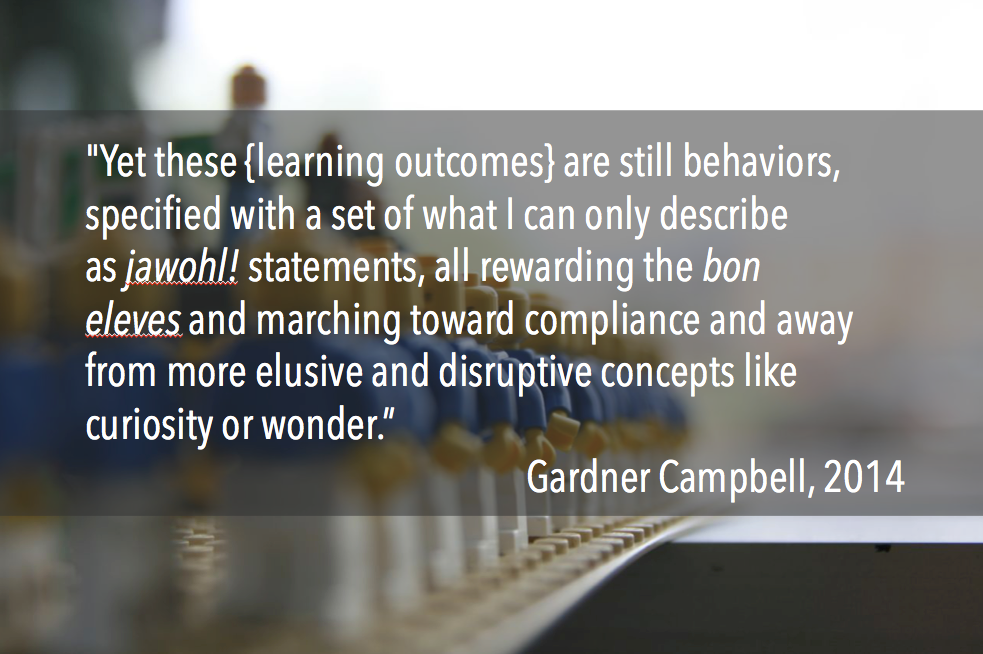

Learning outcomes have become a way in which we decomplexify:

Now before I go any farther, please don’t hear what I’m saying that we should scrap this whole learning thing or that learning outcomes are evil and should be eliminated (Gardner isn’t saying that either, by the way). The purpose of conversations like this is to expose hidden assumptions, hidden power, and what gets lost/hidden when we move to the language of learning. The heavy focus on learning comes with assumptions about for whom and for what education is about and it often obscures the critical questions we should be asking. And it can turn things with good intentions, say learning outcomes, into reductive statements about measurable impact.

The danger here is not just in our classrooms, it’s broader. It’s the potential for people like Kevin Carey, the guy who wrote The End of College, to shape higher education policy. With the decomplexification of education into “learning,” and the decomplexification of “learning” into narrow and measurable objectives, we get to a pretty sad state education that can be easily replaced by third-party providers and unbundled educational commodities.

It’s from these concerns about complexity reduction that Jen Ross and I began to look at alternative approaches to asking critical questions about what is happening in higher education. That’s where not-yetness comes into the picture.

Read more about not-yetness here.

So where does that leave us in terms of teaching and learning…what happens in our classes? When Jen and I first wrote about not-yetness, we talked about the importance of adopting practices that keep complexity in our educational processes, to dwell in uncertainty in a way that helps us to see what’s possible. For those of us who are doing digital pedagogy, this is the critical part. This is the part of questioning, rather than always solving. It’s the willingness to try things that are not perfectly clear where they will end up. That’s hard to do.

We have to rethink our approaches to and views of education. I love this quote from George Siemens because it reiterates the point that we should make space for things that don’t fit into our tidy conceptions about education. Biesta would also argue that we should be looking into, inquiring into, the purpose of education and the relationships of educators and students, which have seemed to have been diminished in the intense focus on learning. When we embrace not-yetness, we should not just look at it in terms of process, but also not-yetness in the purposes of education. For example, we could probably name several purposes of education (jobs, citizenship, socialization) and sometimes those purposes could be at odds with each other. Not-yetness invites us to savor those tensions as fertile opportunities for better understanding education as a whole. Same with relationships with students. Biesta says that the focus on learning has decontextualized education from the teacher/student relationship. Not-yetness invites us to place more value on teacher/student relationships by embracing the messiness and under-determinedness of those relationships.

In my next post, which will include notes from the second half of my AUC-DigPed keynote, I’ll talk about not-yetness & love (and dancing!).

This is great, Amy. It reminds me that there are two meanings of learning, which we can express somewhat inelegantly as LEARNing and learnING.

LEARNing, which you see in such phrases as “increases student learning”, is learning as product, transfer, competency, outcome. And that’s important stuff. But by and large, I think there’s probably enough people pushing that agenda.

LearnING on the other hand, is learning as activity, here it’s like running or dancing or any other gerund. You like “dancing” or you go “dancing” but you can’t actually “increase dancing” the way people talk about “increasing learning”.

What’s fascinated both you and I and others throughout our careers from reading Papert to Fink to Siemens etc is that second conception, of learning as an activity that you get better at rather than as an attribute you possess or buy. The dream is that perhaps we could help guide a generation of better learners, which would make the amount of LEARNing acquired by them in their brief stay with us insignificant by comparison. Hippies, I guess. 😉

Ah, this makes me sad that I am only now reading your work. But thank goodness for digital archives, right? Of course, I see what you see and comment on some of these trends every now and again. I also work in a school with real, live children. And while all this meta-stuff is going on at the theory and policy level, children remain remarkably consistent, I observe, in their inherent embrace of not-yetness in their very beings. In my classes I must recognize that they are always learning *something* – whether or not that particular learning corresponds with my lesson objectives or some abstract standard is another story entirely. Children are pretty determined when it comes to being who they are in a variety of contexts. In so many ways they buck the system in micro and larger ways because that, too, is their job. If we, as teachers could learn to understand that in a more generous appreciation of not-yetness, we might well have communities of learning that are more joy than chore.

Thanks for offering me a new term for framing the impossible endeavor on which I embark week after week: *Teaching* in pursuit of student learning. (Loved the Lego example, by the way!)

Nice article. Not-yetness (the liminal space between being and others) is really the human condition, right? As is our desire to deconstruct. It’s ok (yet uncomfortable) for things to be messy and uncertain. But the other tension between states and markets is a prominent theme here too. Your ngram starting at 1800 would reveal a learning-dominant world pre-1880ish. The rise of mandatory formal education would cause the first inflection point.

Meanwhile, what state/market infrastructures, whether formal or informal, will privilege certain groups?