Not-yetness: Examples

Wow, thanks for all of the responses to my first not-yetness post. I love to hear your thoughts and questions about not-yetness so please keep them coming (it’s helpful if you use a #notyetness hashtag). In the meantime, you should read the following posts from colleagues:

Alyson Indrunas (@AlysonIndrunas), NotYetness, Invention, and the Dream/Reality Whiteboard

Jen Ross (@jar), Not-yetness: Research and Teaching at the Edges of Digital Education

I mentioned in the last post that I would share some examples of projects that I think embody not-yetness. Again, please share your thoughts on these and any other projects you think should be here too. It would be great to keep a growing list.

Domain of One’s Own

I have been following Domain of One’s Own for years, but when I heard Jim Groom (@jimgroom) talk about tilde spaces at ET4Online last year, I began to see Domain of One’s Own (henceforth, DoOO) in a not-yetness light. DoOO is a project of personal cyberinfrastructure, a term coined by Gardner Campbell (@gardnercampbell). The idea is to provide space on the web for faculty and students to set up tools and services they want to use (like WordPress, drupal, wiki software,or omeka) allowing, as Gardner says, for them to be “system administrators for their own digital lives.” Reclaim Hosting, a company started by Jim Groom and Tim Owens (@timmmmyboy), makes it pretty easy for universities or individuals to get started with personal cyberinfrastructure (full disclosure: my fabulous blog is hosted through Reclaim).

In many ways, helping teachers and learners set up personal cyberinfrastructures is very not-yet. You are not defining what the end result will be. It can be complex and messy. Things may not go the way you think they could or should. You are asking teachers and learners to decide what they want the technology to do for them. You are helping them break free from templates and course creation wizards (what the heck is the “wizard” bit about anyway? Who has written about technology and the rhetoric of magic? Please share!). Too many of the tech tools we use force a template on digital identities and work—the templated self, cyborg anthropologist Amber Case (@caseorganic) defines—but the personal cyberinfrastructure is undetermined and malleable. You should read more about templated self from Audrey Watters (@audreywatters) in her Domain of One’s Own Hackathon reflection post.

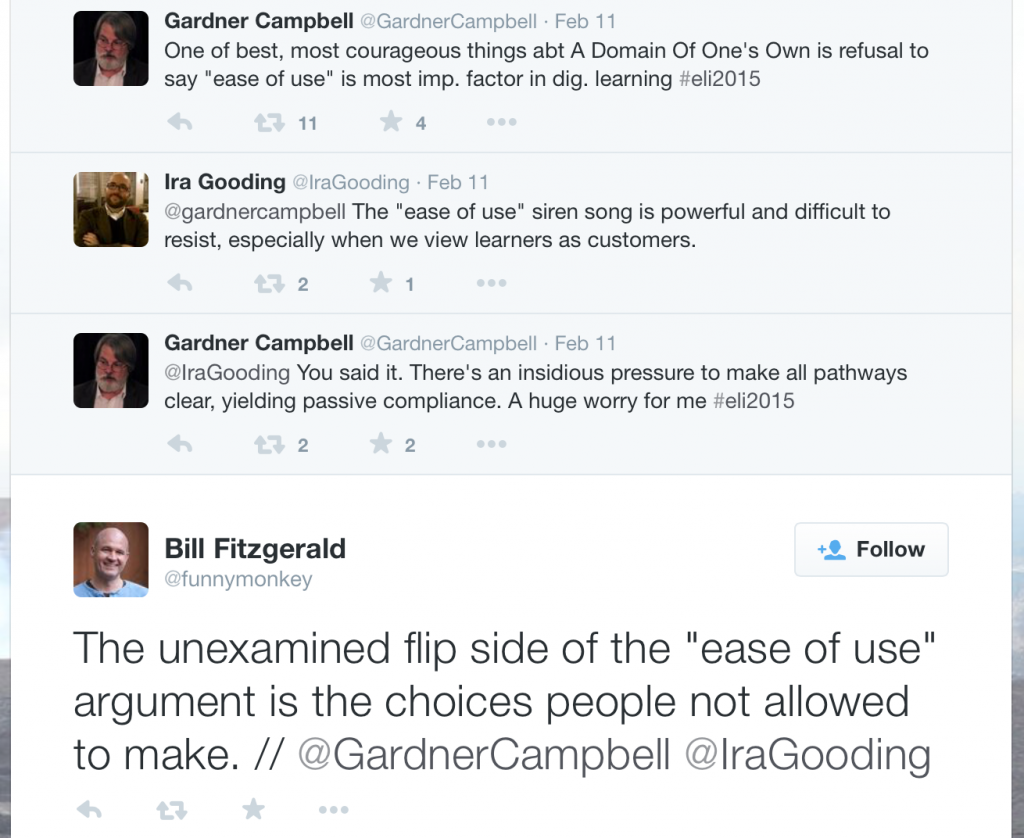

At ELI in February, I heard some folks talking about implementing DoOO at their universities and was even more convinced about its not-yetness. Unlike so many technology implementations on our campuses, DoOO does not exchange complexity and uncertainty for “ease of use.”

At University of Mary Washington, Oklahoma University, CSU Channel Islands, and Emory University, and many other universities, DoOO has led to the evolution of the eportfolio (i.e., what the eportfolio should have been all along), to discussions of digital identity and students’ intellectual property, and to an extensive and varied list of projects led by faculty and students. And then there is one of my favorite implementations—Thought Vectors, a writing course at out of Virginia Commonwealth University that used the same personal cyberinfrastructure idea to have students participate in a vibrant online writing and discussion community. Each section of the course (I’m not totally sure how many there were) had a hub that aggregated work from the students in that section, and the main Thought Vectors hub aggregated work from across the sections and from the public (non-VCU) participants. The openness and not-yetness of the course meant that students had experiences and interactions that were unpredictable from the outset of the course.

Stanford faculty, especially our humanities faculty, have been drawn to this idea. We have a couple of projects starting up that will use this infrastructure, like our Helix courses. These are topically-linked courses that focus on a particular topic (say, food systems or human rights) from different disciplinary lenses. Students in these topically-linked courses will have their own personal cyberinfrastructure to use as they navigate the various courses and learning experiences associated with their Helix. This model also works really well with other teaching/learning approaches that I think are wonderful. Experiential, field-based, service-based learning are all great ways to get students engaged in real world challenges. Domain of One’s Own allows for students to use tools of their choice to journal/document, stitch together, share their experiences and to have those bubble up next to the experiences of other students in the field. Imagine a field notebook that allowed you to not just see other students’ field notes, but to participate in them.

The Happening – Federated Wiki

The Happening is a project my good friend Mike Caulfield (@holden) has been leading. Mike had spent a long time thinking about the problems with wikis, and more deeply, the ways in which the collaboration on the open web works and doesn’t work. For example, there’s a big problem with cross-institutional wikis because they are all site-based, and the group that owns the server or the site sets the rules for contributions to the wiki. And that means when two institutions, departments, faculty, or students collaborate in a single virtual space there can be only one version of reality. You can come to my server, my site, my course space and you play by my rules, my priorities, my vision, my brand. Or I can come to yours and play by yours. Or we can do what we usually do which is say if we have to do this on someone else’s space, forget it.

At Stanford, we encountered these issues while building a course on course design with other organizations that were serving different populations of faculty. Our faculty are different, and one central, editable-by-all, site doesn’t meet our needs. There are local differences that just can’t resolve to a single version, from the level of the institution to the level of the individual. These are places where a forced consensus does violence to diversity of thoughts, needs, and goals. How do you get the benefits of collaboration while not destroying the local diversity you value?

Mike began looking at something called Federated Wiki, which experiments with a crazy idea: what if everyone had their own copy of the wiki, on their own site, but the browser took all these different wiki sites and made them act like one? And if each page would allow you to see other versions of the wikis and adopt them if you liked them. This would mean that versions of pages propagate through many sites rather than resolve to one. You don’t really need to understand much more than that to understand the point I want to make about it. In some ways, the smallest federated wiki is not “ready for primetime.” Its design runs counter to the prevailing designs of how people interact on the web. It doesn’t work the way we know how wikis work. It is, in my view, very not-yet. But Mike has embraced the not-yetness. He invited people around his network and beyond to participate in something he called The Happening. He set sites up for people who wanted to participate, he gave some ideas of things people might do on it, like create a bio page, and then he said, ‘go forth. I don’t know what this thing is going to look like. I don’t know where you will take it.’

And this is where things get really interesting (thank you, I’m here all night). What happened in The Happening surprised even Mike. He recently wrote about some of the topics that emerged and took shape as people interacted within the federated wiki:

What’s great about this experiment too is that it has changed the conceptual space for the problems Mike was trying to solve. At first, he was designing a wiki that would deal with ownership differently…now, he is reimagining how we access, author, and share information.

As Mike said, “You think you’re building technology to solve problems, you’re actually building to help you understand the problems you are trying to solve.” What we are not talking about here is making everything difficult. We are talking about using problems and complexities are opportunities for exciting things. As Mike said, “difficulties are things that slow things down. Problems force you to open the way you do things, to expand conceptual space.” And that means that you can’t really predict where things will end up.

A short list of projects

I could probably write about a dozen other projects but I am not, let’s say, someone who likes to write and so I’m going to list a few projects with brief descriptions below. Again, please send me more examples to write about (yes, I’m volunteering to write more) in future posts.

Rhizomatic Learning – Jen and I talked about Rhizo 14 at our ET4Online plenary last year and are clearly big fans of this project. We highlighted Rhizo because we felt it showed how messiness and complexity can lead to amazing outcomes for learners. The guy responsible for Rhizo 14— and now Rhizo 15—Dave Cormier (@davecormier) has written extensively about it on his blog, so go check it out. What I have said in my recent talks is that what Dave has done with Rhizo is very courageous. He gave up the need to control what happened–the very topic and design of the course is about allowing people to set off in any direction.

What can you do with this? – I haven’t talked about Dan Meyer (@ddmeyer) in a long time, but he continues to be one of my favorite open educators out there. Dan posts videos and pictures (many are his, some are from the community of teachers who interact with him) and asks people to talk about how they would use that resource in their teaching. He is using some clear guidelines for the resources he is sharing (e.g., highly visual, curiosity-raising). I would equate what Dan is doing to what Mike Caulfield described in his “Design Patterns” post; he established design patterns and then opened up possibilities for design implementations. It’s my favorite way to work with faculty—not to saying, “hey, you need some resources, let me give you some problem sets to use” but instead to offer resources that have many possible futures in their classrooms.

Connected Courses and similar MOOCs – You might be saying, “um, Amy, really? MOOCs? How do they embody not-yetness?” And my response is, “um, they started off…no, before 2012…they started off VERY not-yet.” The early MOOCs and a great many since are about exploring the edges of who we call learners and how those learners participate in a community or a network of learning. So, yeah, check out MOOCs like Connected Courses, Phonar, MOOC MOOC, and Human MOOC, to name a few.

As I was writing my notes for the talks I gave, I started wondering what were consistent traits of these projects. Yes, not-yetness and yes, all of the things I put in that embracing not-yetness list in the last post. But what else? One thing I noticed was that these projects are kind of hard to describe. There are elements that are ill-defined and difficult to fully capture. All of these projects embrace the not-yetness of the open web. All of the projects embrace complexity—don’t seek to reduce it. In all of them, the role of the instructor, the role of expert, is still very important—but the projects find ways to synergize that role with the roles of the learners and other experts. And they give students a lot of freedom to explore and push the edges of the learning experience. The resulting student work is surprising in its creativity, play, and engagement. Choice and ownership, no matter how messy and complex choice can be, opens up amazing opportunities for students.

I think it’s important too to think about how to help create the environment and support for not-yetness at our institutions. Experimentation is vulnerable. And embracing not-yetness requires courage, room for forgiveness, and for things to not always be perfect. That’s a conversation we need to be having at our institutions. There is also sometimes a resistance to complexity, because it is confounded with complication. We need to recognize those are different things, talk about the differences, and acknowledge where complexity is useful.

I am not suggesting that everything we do with technology should take the approach of not-yetness. I am suggesting that thinking about not-yetness helps us combat technological implementations that severely limit what we can do, what students can do. I am suggesting that not all of our projects that involve technology have to be perfectly designed and meet set outcomes. I am suggesting that we make space for experimentation, for play, for uncertainty, for forgiveness.

I want to finish this post with a little story. I have given this not-yetness talk a couple of times now. The first time, it was a keynote at an IT conference, so the room was filled with CIOs, CTOs, and IT folks. At the end of the talk, I sat down with my friend Mike Caulfield and asked him for feedback. He said he liked the talk because, “I was able to look around the room and see allies. People with whom I could work, people even on my own campus, with whom suddenly we had something to talk about. Suddenly, I can see where our values aligned.” Turns out, someone at his table was another person from another branch of his university system with whom he was able to start a conversation about these ideas. Then I received an email, just a few hours after my talk, from another such ally. He thanked me for the talk, saying, “My own CIO asked how we take these concepts home and start implementing them.” He then said that his conversation with the CIO felt very much like the second time I gave my son the Legos, without the instructions. He described his conversation as such:

CIO: “How do I change our behaviors to make education better?”

Him: “Use your imagination!”

CIO: “How do I develop imagination?”

Him: “Try things, observe, eliminate boundaries, be patient!”

CIO: “Yea yea, patience, how long will that take me?”

I think we have a lot of work to do, but I hope that this is just another spark in a larger conversation. I hope you find allies in this conversation. Yes, there are a lot of constraints—people raise concerns about everything from accreditation to promotion, to support, to security—we need to talk about those things too. But I hope you also find allies. You certainly have an ally in me.

It strikes me that most of these projects—the ones that involve courses, as some of us continue to be required to teach, anyway—are large scale. That’s not a bad thing. But I wonder what those of us do who don’t have that audience (or the power to draw them) to both allow for not-yetness while still meeting institutional objectives (sad to say, they still exist) and facilitating a good experience the 10-15 students who are paying tuition when so much of that experience seems to stem from the scale—a population large enough to have enough powerful actors to *have* a learning community that functions like these examples.