The power of making

In third grade, growing up in Brazil and homeschooled through a correspondence school called Calvert, I found that my opportunities for scientific inquiry were, shall we say, limited. Yet, like most children, I was obsessively inquisitive, teaching myself how to pick locks, taking apart radios, assembling periscopes, and more.

I remember reading Smiling Hill Farm, a story about three generations of western settlers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In the book, the matriarch of the family makes soap using animal fats. I did not have easy access to animal fats (yes, even in Brazil) so I procured my mother’s talcum, lotion, perfume, and glue and made my own soap. As you can imagine, this was not a successful venture, but from that experience (and several conversations with my mother while washing dishes), I learned about oils and lipids and how I might be able to make my own soap, with access to the right ingredients.

I think about that experience now that I am a parent of a curious and capricious 3-year-old. I see in Vaughn the same burning desire to create, experiment, push boundaries, and learn. Jonah Lehrer called young kids “natural scientists” and I agree with him. Curiosity…that desire to understand, the desire to test things…is a powerful driver for kids’ interests and learning.

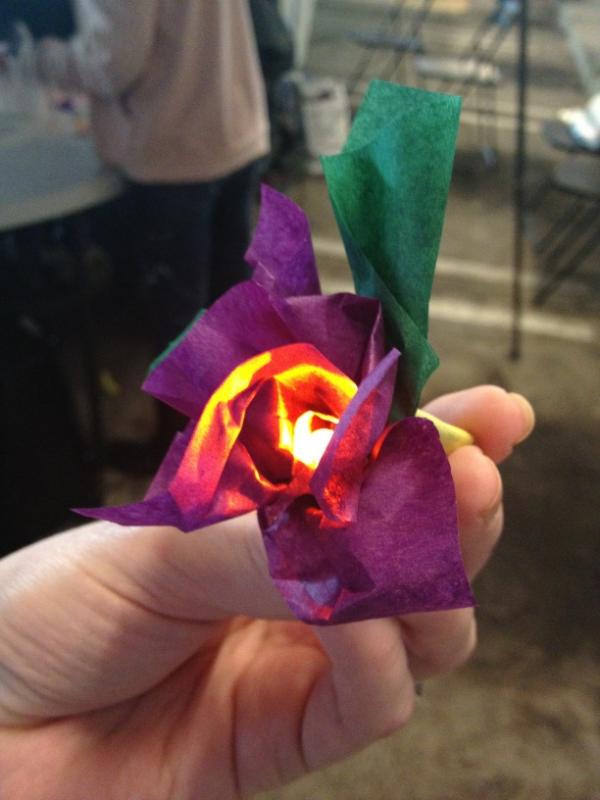

This is one reason the maker movement appeals to me and why I loved events like the Super Happy Block Party. Making requires hypothesizing, testing, analyzing, and adjusting. It requires creativity, learning from failure, and feedback. It requires problem-solving. I was shocked to see an 8-year-old boy soldering a circuit board at the Super Happy Block Party. I wasn’t shocked because I thought he was too young; I was shocked because I was witnessing the powerful learning that can be fostered when we give kids tools and opportunities to make.

When I look at formal education, I don’t see many classes built around problem-solving and fewer still around making. This applies to both K-12 and higher education classes, with exceptions in each. It’s strange to me that we don’t see more making in our classes, since making leads to evidence. Factoids alone–which are typically what we cover and assess in class–don’t show us whether students have learned. But when we see students “recruiting facts as tools to solve problems” (as James Gee so beautifully said), and making physical or digital solutions to problems, we see evidence of learning.

How can we build making into our students’ learning? Here are some suggestions I have collected from various educators I admire:

- Put makerspaces in schools and university buildings. In the DML 2012 session “Learning through Making: Opportunities and Challenges for a Maker Culture,” the panel suggested that schools should have makerspaces equipped with creating tools like 3D printers, power tools, sewing machine, and all kinds of materials. Electronic tools like Arduinos and circuit boards are also useful. For information about what equipment might be included in a makerspace, check out this list from makerspace.com.

- Build curricula around solving real-world, meaningful problems that require creative solutions. Then set students loose on those problems. Sadly, we often think of this learning experience as restricted to Science and Engineering courses. What about in Education and Humanities courses? Can Education students solve learning space issues at a university by building 3D models of classrooms? Can English students code a program to identify common grammar mistakes in students’ papers? Can History students design and build a model for a monument for the Mall in Washington DC? I can’t take credit for that last idea; that is what Heather Pang is planning to do with her History students at Castilleja School (they’ll be doing this in their FabLab, by the way; more on FabLabs here).

- Bridge making that happens outside and inside of the classroom. Sometimes the things that engage us the most are not in the classroom. (WHAT??!?!) As teachers, we can look for ways to encourage building outside of the classroom that supports what happens inside the classroom, and vice-versa. I’m reminded of a video I saw at DML 2012 about a young man who built a secret-knock gumball machine at home with help only from a copy of Make magazine that someone left on a table where he worked. It’s a powerful video and it reminds us of how important informal learning is. We know that we see a growing gap in achievement between lower socioeconomic (SES) students and higher SES students during the summer because higher SES students are more likely to have access to rich informal learning opportunities during that time away from formal learning. Can “making” projects ameliorate that summer-related achievement gap?

- Create maker clubs. Stanford has an active (and very cool) maker club. Again, we see an opportunity to bridge informal and formal learning by fostering the development of these maker clubs and, perhaps, creating assignments in courses that make use of maker club resources and communities. Here is a list of Young Maker clubs along with tips for starting new clubs.

This post is already too long but, before I finish it, I want to share with you a brand-new hacker/makerspace in the Bay Area. It’s the Mothership HackerMoms hacker/makerspace and its goal is to give mothers a space (with childcare!) to create. I am excited to check it out soon, so I will report back on what I find. Oh, and don’t forget that the Bay Area’s Maker Faire is coming up! May 19-20 at the San Mateo Event Center. Don’t miss it!

One Response